Because conservatives agree with Musk about the importance of making social media a welcoming place for transphobic jokes, they haven’t been nearly as quick to condemn him telling the Financial Times that Taiwan ought to become a Beijing-ruled Special Administrative Region. But when it comes to a random celebrity like John Cena, conservatives understand the basic dynamic perfectly well — money talks.

But this applies to corporate entities like Apple and Mercedes-Benz even more than it does to individuals like Cena. An individual always has the option of voluntarily earning less money in order to take a principled stand on human rights. If Apple executives started “doing the right thing” in a way that seriously impaired the company’s stock price, they’d be vulnerable to activist investor campaigns and potentially even litigation.

This strikes me as a fairly profound policy problem. Part of the promise of the old bipartisan consensus in favor of trade with China was that economic integration would help spur the export of American speech norms. Not only has that not worked out, but the practical consequences have been the opposite. I’m sure that if you asked Intel executives whether it’s good that China is perpetrating a genocide and using forced labor in Xinjiang, the vast majority of them would say, in private, that it’s actually bad. But in practice, Intel has apologized for past statements about Xinjiang. Because for all the virtues of capitalism and the for-profit business corporation, it also has at its core an amorality that can produce really bad results when it interfaces with a large despotic regime.

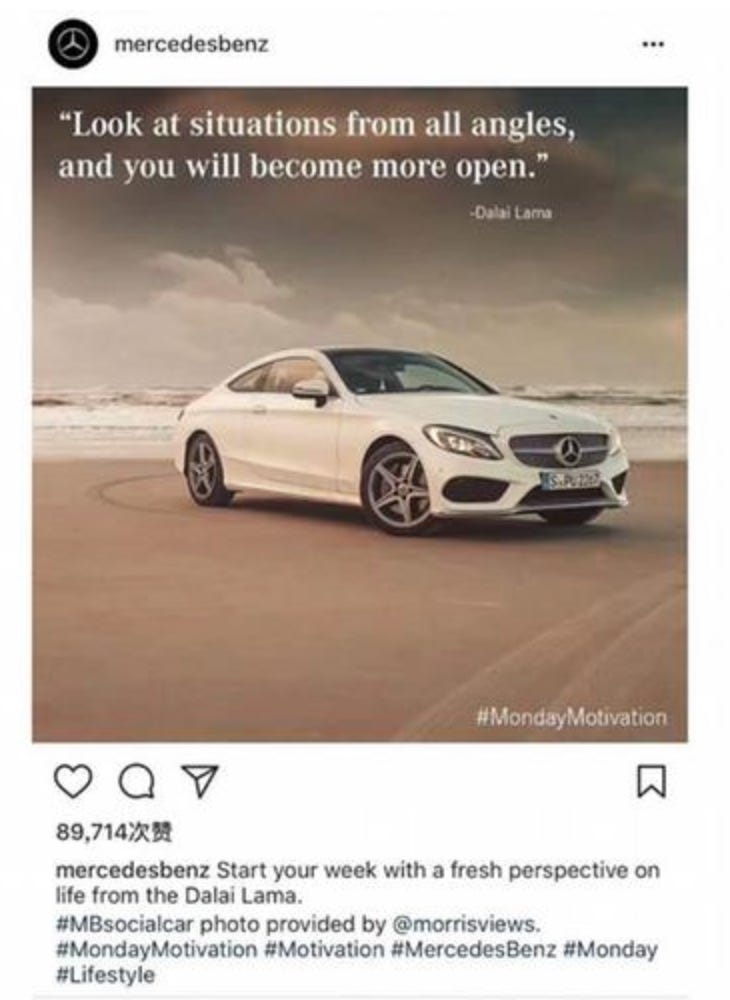

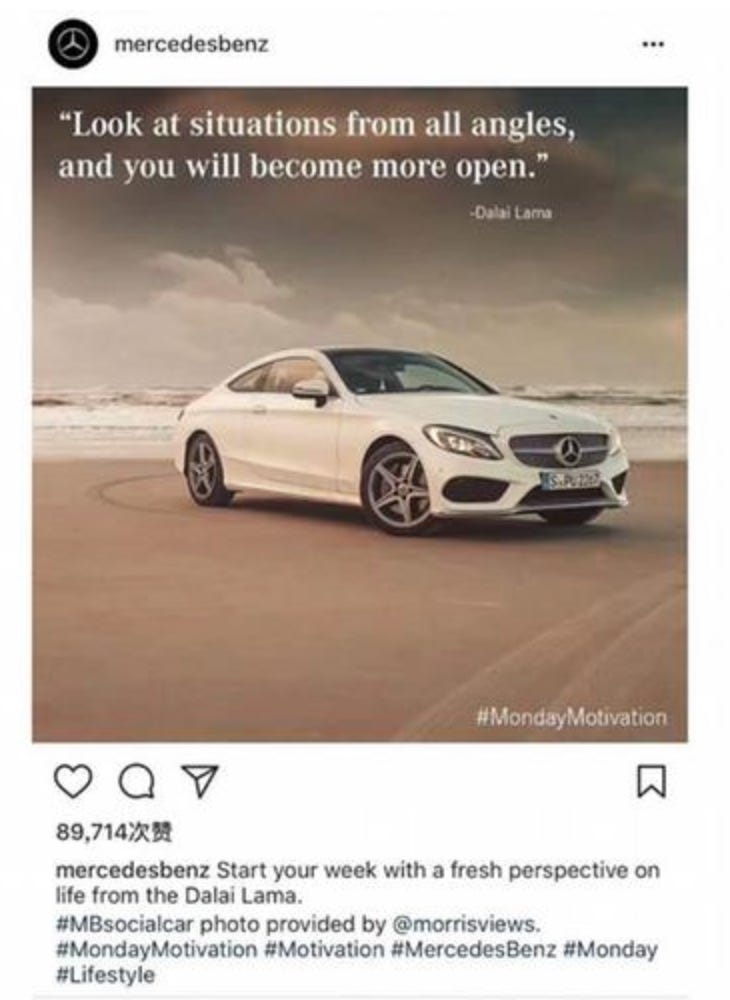

The global electronics industry is famously exposed to the China market. But as we saw with Mercedes Benz, China is a really big deal for automakers as well. Tesla is setting sales records in China, which is obviously only possible because the Chinese government lets Tesla sell cars there.

Like many global manufacturing companies, Tesla also builds things in China — including what Musk projects will be the company’s largest factory in the world.

There’s nothing particularly untoward or suspect about this. Many more people live in East Asia than live in North America, so it’s natural that over the long term any manufacturer of large objects is going to want to have their biggest production facilities in Asia.

But Tesla has received unusually generous treatment from the Chinese government. Part of China’s strategy for industrializing has been to say to foreign companies operating in key sectors that if they want to be in the China market, they need to operate as a joint venture with a Chinese-owned firm. It’s become pretty clear that this is a mechanism for Chinese companies to learn foreign technology and business methods, and ultimately pull Chinese-owned companies up the value chain. Foreign companies don’t like it, but in most cases the lure of the China market is just too good to resist. Telsa, though, managed to become the first automaker to receive an exemption from the joint venture requirement.

That’s a huge coup for Musk and a testament both to the quality of Tesla’s products and also to Musk’s shrewdness and skill as a businessman. But without being a hater, I have to say that “shrewdness and skill at making Xi Jinping like you and want to give you favorable treatment” is a mixed ethical bag. The New York Times is blocked in China as part of their censorship regime. So is Substack. It would be better for their businesses if A.G. Sulzberger and Chris Best were as skilled as Musk at getting Xi to do special favors for their companies. But achieving that goal would require them to fundamentally compromise the integrity of editorial businesses in a way that I think would outweigh the benefits. More fundamentally, as a non-corporate person, I would be thrilled to have Chinese readers but also profoundly embarrassed if this site managed to become popular in China without getting censored. That would suggest I’m doing a really bad job of standing up for core values that Americans on the left and right broadly agree on.

Ten years ago, Tesla was a very small company that Mitt Romney denounced as the kind of “loser” that was dependent on unwise subsidies from the Obama administration. At the time, liberals were generally enthusiastic about the idea of an electric vehicle startup. And to the extent that Musk had any known political views, he seemed like a pretty mainstream Democrat.

He also had very normal geopolitical opinions like “foreign dictatorships are bad” that a person who doesn’t have extensive Chinese business interests is free to express on Twitter (which, of course, is banned in China).

But as Musk’s business grew, he became more China-friendly in his public statements. Initially this took the relatively sensible form adopted by many who need to come up with something nice to say about the PRC: praise for their extensive infrastructure buildout. This is something I’ve done myself — it’s incredibly impressive that China built mid-sized metro systems in a couple of dozen cities over the course of time that it took the United States to build three miles of subway on the Upper East Side.